| Archer Alexander is a part of US Black history. Join: US Black Heritage Project Discuss: black_heritage |

Biography

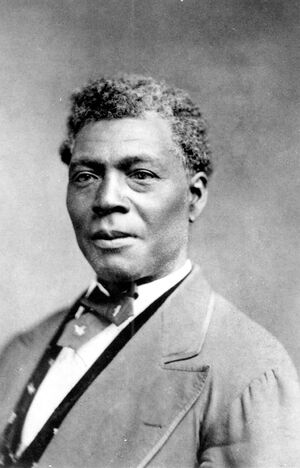

Archer Alexander, the model for the emancipated slave in the 1876 Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., was the last fugitive slave captured under civil law in Missouri and the subject of an 1885 biography, The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom, March 30, 1863, written by his prominent abolitionist friend and protector, William Greenleaf Eliot.[1]

With many details of his own story lost to him through slavery, what was known about Archer Alexander until 2009 came from that 1885 biography, written mostly from Eliot's recollections of Archer's remembrances, six years after his death. In 2009 a thirty-year research project by a descendant, Errol D. Alexander, PhD., The Rattling of the Chains: the True Story of an American Family, unveiled new details of Archer's life.[2]

Archer Alexander was thought to have been born about 1810 on the plantation of the Rev. Delaney Ferrell family in Fincastle, Virginia, the son of slaves Chloe and Aleck Prince.[3] But according to research, Archer's mother was owned by-- and Archer was an unacknowledged son of-- John B. Alexander or his son, James H. Alexander, and born in 1816. As a mulatto child, Archer was given the last name of Alexander and the slightly higher status of indentured servant to John Alexander by the wardens of the Presbyterian Church.[4] He was later sold to Delany Ferrell, inherited by his son, then sold to Louis Yosti, and then to Richard Pittman in 1844.[2]

According to W.G. Eliot's book, in 1827, the only father figure he'd known, Aleck Prince, was sold by Ferrell to pay off debts while Archer was still a child, and was never seen by him again; his mother died in 1831 soon after Archer was taken away to Missouri by Thomas Ferrell, and hired out by him. Archer worked for Richard Pittman for more than twenty years as an overseer on his farm in St. Charles County, on the Missouri-Kentucky border.[2]

During that time, c.1837, he married an enslaved woman named Louisa, owned by neighboring farmer James Naylor [according to Wikipedia. But Eliot says his name was Hollman, and that Hollman later bought Archer from Thomas Ferrell.] Over the years, Archer and Louisa Alexander became the parents of ten children, some of whom Naylor [Eliot says Hollman] "sent away" because of their behavior.[1][5][2]

Their known children:

- Thomas Alexander (c.1839-c.1863)

- (c.1841)

- (c.1843)

- (c.1845)

- (c.1847)

- (c.1849)

- (c.1851)

- Ellen "Nellie" Alexander (c.1853)[5]

- James Alexander (c.1855)

- Alfred Alexander (c.1862)[2]

In 1863, Alexander heroically notified a Union informant that a bridge they intended to use had been sabotaged by Confederate sympathizers. Under suspicion of being the informant, he fled the farm, but was captured. He escaped and returned to St. Louis,[6] where he met the Eliots, who gave him a job and sanctuary. Eliot obtained legal protection for him, but in violation of it, a group of slave-catchers took him by force, beat him, and held him until Eliot, with the help of the provost-marshal and his soldiers, freed him before they could leave again for Kentucky.[5]

On January 11, 1865, all slaves in Missouri were freed, and Alexander, his wife, and some of their children were reunited. In 1866, Louisa decided to return to Naylor's house for items she had left behind. She died there.[1]

The following year, Alexander married a woman named Julia. The newly married couple moved into their own rented house, and were counted on the 1870 census with their blended family in Joachim Township, Jefferson, Missouri.[7]

After Lincoln's assassination, Eliot and the Western Sanitary Commission, a St. Louis-based volunteer war-relief agency, worked to build a statue of Lincoln. The funding for an Emancipation Memorial in Washington D.C., featuring a statue of Lincoln, began with a $5 donation from a former slave, Charlotte Scott, from Virginia. All of the initial funds raised were from donations from former slaves, later matched by donations from the WSC.[8][1] Sculptor Thomas Ball had a model made, but Eliot's group, wanting a real freedman to pose for it, chose a photo of Archer Alexander for the model, which was unveiled in 1876.[1]

|

| Archer Alexander |

|

| Emancipation |

His wife Julia died at age 39 in 1879, one year prior to Alexander’s death in St. Louis, Missouri in 1880. Archer spent his final days in Eliot's household.[9] Archer Alexander died sometime after 9 June 1880 in St. Louis, Missouri.[9]

According to DNA research from 23&Me, Muhammad Ali's paternal grandmother was Alexander's great-granddaughter, making Ali the great-great-great grandson of Archer Alexander.[10]

In 1940 a U. S. stamp honoring Alexander was issued as part of the Black American Commemorative series. In 2014 Washington University established the Archer Alexander Distinguished Professorship with Dr. Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp as its inaugural Professor.[3]

Archer was mentioned on a memorial in Saint Peter's Cemetery, Normandy, St. Louis County, Missouri, United States with a death date of 8 December 1880.[11]

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wikipedia contributors, "Archer Alexander," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Archer_Alexander&oldid=1063491821 (accessed February 10, 2022).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Liam Otten, "Of Friendship and Freedom: The histories of Archer Alexander, a fugitive slave, and William Greenleaf Eliot Jr., the university’s first president, intersect in a dramatic and inspiring story of courage and compassion," Washington University Magazine, (St. Louis, MO: Washington University, 6 May 2016)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Susan J. Griffith, "Alexander, Archer (ca. 1810-1879)," at the Online Encyclopedia of Significant People and Places in African American History (BlackPast.org); published 2011.

- ↑ Errol D. Alexander, PhD., The Rattling of the Chains: the True Story of an American Family, Vol. 2, chapter 26.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 William Greenleaf Eliot, The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom, March 30, 1863, Electronic Edition

- ↑ Wikisource contributors, "The Biographical Dictionary of America/Alexander, Archer," (Wikisource: 21 May 2022 19:08 UTC, retrieved: 21 May 2022 19:08 UTC), The Biographical Dictionary of America/Archer Alexander, Johnson, Rossiter, ed., "Alexander, Archer," The Biographical Dictionary of America, Vol. 1, (Boston, MA: American Biographical Society, 1906) p. 74.

- ↑ "United States Census, 1870", database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M46D-XTB : 19 March 2020),

- -Archer Alexander M 54 Virginia

- -Julia Alexander F 30 Mississippi

- -James Alexander M 14 Missouri

- -Dora White F 12 Missouri

- -Alfred White M 8 Missouri

- -Ellen Alexander F 17 Missouri

- ↑ William E. Parrish, "The Western Sanitary Commission," Civil War History, Vol. 36, Issue 1, (March 1990) pp. 17–35.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M6NH-R8L : 14 January 2022), A. Alexander in household of William Eliot, St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, United States; citing enumeration district , sheet , NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm.

- - William Eliot M 64 Massachusetts, United States

- - Abbie A. Eliot F 62 District of Columbia, United States

- - Cristopher Eliot M 24 Missouri, United States

- - Edw. C. Eliot M 22 Missouri, United States

- - Ross Eliot F 18 Missouri, United States

- - Wm. Comstock M 22 Massachusetts, United States

- - Delia Gedur F 21 Ireland

- - Mary Wiry F 20 Ireland

- - A. Alexander M 65 Virginia

- ↑ "DNA evidence links Muhammad Ali to heroic slave, family says Ben Strauss," Washington Post, October 2, 2018.

- ↑

Memorial:

Find a Grave (has image)

Find A Grave: Memorial #87503002 (accessed 20 October 2022)

Memorial page for Archer Alexander (1806-8 Dec 1880), citing Saint Peter's Cemetery, Normandy, St. Louis County, Missouri, USA (plot: Section: 10, Block: X, Lot: 388.00, Grave: 1); Maintained by Tami Glock (contributor 46872676).

See also:

- Lawrence O. Christensen, Dictionary of Missouri Biography, (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1999)

- Wikipedia: [wikipedia: Archer_Alexander|Archer_Alexander]]

- Wikidata: Item Q4785939, en:Wikipedia

No known carriers of Archer's DNA have taken a DNA test. Have you taken a test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Featured Eurovision connections: Archer is 33 degrees from Agnetha Fältskog, 25 degrees from Anni-Frid Synni Reuß, 28 degrees from Corry Brokken, 21 degrees from Céline Dion, 24 degrees from Françoise Dorin, 27 degrees from France Gall, 29 degrees from Lulu Kennedy-Cairns, 25 degrees from Lill-Babs Svensson, 23 degrees from Olivia Newton-John, 35 degrees from Henriette Nanette Paërl, 34 degrees from Annie Schmidt and 21 degrees from Moira Kennedy on our single family tree. Login to see how you relate to 33 million family members.

A > Alexander > Archer Alexander

Categories: USBH Heritage Exchange, Linked | US Black Heritage Project, Needs Profiles Created | Saint Peter's Cemetery, Normandy, Missouri | USBH Heritage Exchange, Needs Slave Owner Profile | USBH Heritage Exchange, Needs Plantation Page | Virginia, Free People of Color | Botetourt County, Virginia, Slaves | Persons Appearing on US Postage Stamps | St. Louis, Missouri | Fincastle, Virginia | US Black Heritage Project Managed Profiles | African-American Notables | Notables

He is being honored in St Charles on Saturday, September 24, 2022.

edited by Carole (Kirch) Bannes