Contents |

Biography

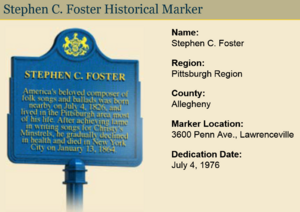

Stephen Collins Foster, known also as "the father of American music", was a beloved American composer and songwriter.

Early Life

It is tempting to say something melodramatic about Foster's birthdate, 4 July 1826, the 50th anniversary of the founding of the United States and the day that the last two of its Founding Fathers (Thomas Jefferson and John Adams) passed away.[1] Living in the period between the Revolution and the Civil War, Foster came of age with his country and struggled with many of the same issues the country did. In doing so, he was a formative influence on American culture and has been called "The father of American music."[2]

Stephen was the ninth of ten children born to William Barclay and Eliza Foster. They would lose two children as babies, one of which was the youngest, James, who died when Stephen was under four years old. This means that Stephen was always the baby in a very large family.[3] The family was prosperous and, along with his siblings, Stephen was given a broad, classical education.[4] He was a good student and excelled in music, teaching himself clarinet, guitar, flute, and piano.[2]. It is unclear how much instruction he received. His brother pictures him as a musical genius, picking up a guitar at the age of two and producing beautiful music from a flute the first time he picked one up, aged seven.[4] Perhaps a brother can be forgiven some exaggeration about his famous sibling. However, it is clear that Stephen learned a number of instruments well and studied classical composers like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and others, on his own time.[3]

As a young man, Foster was writing minstrel songs like "Uncle Ned" (a precursor to "Old Black Joe") and "Louisiana Belle." But he wasn't moving forward in what his family saw as a career, so they insisted he get to work. Therefore, he moved to Cincinnati, where he served as a bookkeeper for his brother, Dunning for two years (1846-1848). His work there was excellent, but uninspiring.[3]

Musical Career

The song "Oh! Susanna," was written while Foster was in Cincinnati working with his brother. It was published by W. C. Peters in 1848 along with "Uncle Ned" and "Away Down South".[3] "Oh! Susanna" is one of the most popular songs that Foster ever wrote -- in fact, one of the most popular songs in American culture. As a result of its popularity, Foster became determined to make a living as a composer and soon became "the first fully professional songwriter in the United States."[5]

The decision to become a professional composer changed the course of Foster's career and, to some extent, the content of his music. His earliest music was tied to black-face minstrelsy and contained many of the racist features of that kind of music. Dialect is used, as in the chorus of "Uncle Ned," "Den lay down de shubble and de hoe" and the use of the n-word.[6] The lyrics of "Oh! Susanna" are also in dialect (in the original) and nonsensical. For example, one lyric is "It rained all night the day I left / The weather it was dry. The sun so hot / I froze to death. Susanna, don't you cry." The n-word is also used here.[7] Thus, whether to celebrate the song as a fundamental part of the American songbook, or relegate it to the dustbin, has been a quandary. Wikipedia tells us it is "among the most popular American songs ever written" and points out that "[m]embers of the Western Writers of America chose it as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time."[5] Stephen's brother points out the popularity of the song,[4] but Milligan derides it as minstrelsy, in which African-Americans were presented as "a buffoon, a crude caricature" and in which "gibberish had become a staple of composition, the wit of the performance consisting largely in the misuse of language."[3].

Foster himself referred to these earlier works as "miserable songs" and seemed unaware of the amount of money he could make from them, allowing others to publish them under their own names.[3] However, as his popularity grew, he began to seriously work to write music that appealed to the class of people he grew up with (middle-class and above) and to manage the publication of his music more carefully. He moved home, set up an office in his parents' house, and became a full-time composer. He also began to manage the business side of his music, working to regain copyright to songs that were being performed by various minstrel groups (and presented as their own compositions) and to secure a publishing contract with Firth, Pond, & Co.[4]. His initial output during this period was astounding; he published sixteen compositions, including the perennial favorite, "Gwine to Run All Night" (also known as "Camptown Races")[8]

Marriage

Foster was settling down -- turning his music into a profession and getting married. Stephen married Jane D McDowell, the daughter of a prominent Pittsburgh physician, on 22 July 1850 in Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States.[9][3] The following spring, their only child, Marion, was born.[10].

Little Marion was not the only production of 1851. Foster again had a banner year, publishing seventeen songs, including "Old Folks at Home" (sometimes called "Way Down Upon the Swanee River"),[8] which is now the state song of Florida.[11]

With things moving forward, the little Foster family moved to New York City, where opportunities to further his career seemed brightest. However, within a year, Foster became homesick (according to his brother), and rapidly uprooted his wife and child and hustled back to Pittsburgh, arriving unexpected in the middle of the night, but welcomed by his mother with open arms.[4] Other biographers note that "the date, circumstances and length of this sojourn in New York are shrouded in mystery," although it is clear that Foster was living in New York and not just visiting, based on a letter written home to his brother Morrison on 8 July 1853.[3]

A Tragic Year

Stephen did seem to be living at home when his mother died in January 1855.[12]. His father died a few months later.[13] Further tragedy came when Stephen's brother, Dunning, died in March of 1856, at the age of 35.[14]

One wonders whether these losses, especially the loss of his mother, led to the decline in Stephen's musical output. As noted above, Foster published seventeen songs in 1851. In 1852, he published four songs, including "Massa's in de Cold Ground." In 1853, he published nine. One of those was "Old Kentucky Home," which later became the state song of Kentucky.[15] His creative streak continued in 1854, with "Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair" and eight other songs. But in 1855, he published five song, in 1856, three, and in 1857 only one. Note -- a publication date is not the same as the date the song was written. The songs may have been written well before they were published, but the publication history does give a sense of when Foster was especially productive -- and when he wasn't.

Although Foster's career seemed in danger of stalling, something important was happening in some of the songs he wrote. His ability to capture the human condition and to demonstrate the emotions of human life, long a feature of the parlor songs, was combined with his writing about Black Americans -- still enslaved at this time. The pathos of "My Old Kentucky Home" was appreciated by none other than Frederick Douglass, who said the song "awakens sympathies for the slave, in which antislavery principles take root, grow, and flourish."[15]. However, it should be underscored that Foster himself was not an abolitionist.[3]

Final Years and Death

In the last four years of his life, Foster moved to New York City, moving there in July 1860. His wife, Jane, and daughter, Marion, stayed behind in Pittsburgh for much of that time. Milligan notes that one writer said that he met Foster in New York in 1861 and that, at the time, his family was also living in New York City. However, his wife was not with him when he died in 1864. At some point his family went back to Pittsburgh. At the same time, many of the memories recorded by others after Foster's death stretch the truth.[3] His brother, Morrison, barely mentions these years, jumping from Foster's move in 1860 to his death in 1864 in the space of one sentence.[4]

These were productive years, however. Foster had a new contract with a second music publisher, which he mentioned to his brother in a letter from April 1860.[3] His publication rate picked up, as he continue to publish songs with Firth & Pond, as well as with John J. Daly and Horace Waters -- as well as others. During these four years, he published eighty-nine songs, including the haunting "Old Black Joe." Many more songs, including "Beautiful Dreamer" were published after Foster's death.[8]

The United States Civil War broke out in 1861, and Foster's songs (many of them with lyrics by George Cooper) addressed the conflict. Some titles include "Was my Brother in the Battle?" "For the Dear Old Flag, I Die," and "The Soldier's Home." Stephen's complicated presentation of the racial identities of Americans is evident here. As noted above, Foster had the ability to reach deep into the human heart and speak our deepest feelings. Although he wrote many minstrel songs that caricatured African-Americans, falling prey to demeaning stereotypes, he could also express the pain and agony of enslaved people separated from loved ones, perhaps due to being sold away, (as in "Old Kentucky Home") or the longing to reunite with those who had died, as in "Old Black Joe." However, Foster's music continued to use the old stereotypes. Granted, many of the lyrics in this period were written by George Cooper, but Foster implicitly endorsed them by setting them to music. Compare "Willie's Gone to War" (1862) with "A Soldier in the Colored Brigade" (1863). "Willie has Gone to War" is one of a series of "Willie" songs (the choice of name possibly relating to his father or his brother, both named William Barclay Foster). The lyrics here have all the sentimentality of the parlor songs; the chorus is:

- Willie has gone to the war,

- Willie, Willie, my lov'd one, my own;

- Willie has gone to the war,

- Willie, Willie, my lov'd one is gone.[16]

On the other hand, "A Soldier in de Colored Brigade" includes the use of dialect and cariacture, familiar from the minstrel shows. The message, however, is more complicated. While the narrator speaks of how he will quickly become a colonel and get paid in greenbacks -- as if that is all he desires -- and ends his song with a promise to "raise up picaninnies for de colored brigade," there is also an inclusion of history and law, speaking to the importance of Black Americans. The fourth verse details African-American participation in the country's wars from the Revolution onward and the third verse sets out a righteous cause:

- Wid musket on my shoulder and wid banjo in my hand,

- For Union, and the Constitution as it was I stand.

- Now some folks tink de darkey for dis fighting wasn't made,

- We'll show dem what's de matter in de Colored Brigade.

However, in the fifth verse he warns abolitionists to leave the Blacks alone for fear of losing the Union their forefathers had made -- a Union worth more than "20 million of de Colored Brigade."

The lyrics are confusing, but the music Foster wrote for Cooper's lyrics underscore the difference between the sweetness and love shown to a White soldier and the buffoonery of the African-American soldier. "Willie has Gone to the War" is sweet and lyrical; "A Soldier in de Colored Brigade" is a brisk, dance hall number.

Foster was churning out songs at an amazing rate, but was also -- if Cooper's reminiscences are accurate -- he was selling them outright as soon as he wrote them. "Willie Has Gone to War" was sold for $25.[3]

Most of these songs are not memorable, besides the aforementioned "Old Black Joe" (1860) and "Beautiful Dreamer" (1864, posthumously).

In January of 1864, Stephen was discovered in his room by the maid lying in a pool of blood. A broken washbasin was nearby and he had a deep wound in his neck. George Cooper arrived and took Stephen to Bellevue hospital. Cooper wrote to Stephen's brother Morrison:

- New York City, January 12, 1864

- Morrison Foster, Esq,

- Your brother Stephen I am sorry to inform you is lying in Bellevue Hospital in this city very sick. He desires me to ask you to send him some pecuniary assistance as his means are very low. If possible, he would like to see you in person.

- Yours very truly,

- George Cooper

Morrison did not make it to New York City in time. On the 14th, Cooper telegrammed, "Stephen is dead. Come on."[3]

Stephen's brother explains his death as the result of some kind of flu or head cold. Weak from the illness, Stephen attempted to wash up, tripped, and the broken glass of the wash basin cut him.[4]

The funeral was held 21 January 1864 at Trinity Church, Pittsburgh. Foster is buried in Alleghany Cemetery in Pittsburgh.[17][18]

Posthumous Honors

The "1-cent Foster single stamp" issued by the US Postal Service in his honor, 1940.

In 1970, he was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. [19]

Sources

- ↑ I can, perhaps, be forgiven this melodrama as both his brother, Morrison Foster, and Harold Vincent Milligan make note of the meaning of the date, as well.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wikipedia contributors. "Stephen Foster." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 22 Sep. 2022. Web. 26 Sep. 2022.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Milligan, Harold Vincent. Stephen Collins Foster: a biography of America's folk-song composer. Schirmer, 1920. Google Books

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Foster, Morrison. My Brother Stephen privately printed, 1932.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Wikipedia contributors, 'Oh! Susanna', Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 5 September 2022, 22:44 UTC, accessed 27 September 2022 link to Wikipedia article

- ↑ Foster, Stephen. "Uncle Ned," Song of America,

- ↑ Foster, Stephen. "Oh! Susanna," Song of America,

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wikipedia contributors. "List of songs written by Stephen Foster." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 29 Sep. 2022. Web. 18 Oct. 2022.

- ↑

Marriage:

"Pennsylvania, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Marriage Records, 1512-1989"

FamilySearch Record: 6CYF-FRD2 (accessed 26 September 2022)

FamilySearch Image: 3Q9M-CS7S-JXQ8 Image number 00020

Stephen C Foster marriage to Jane D McDowell on 22 Jul 1850 in Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States. - ↑ "Find A Grave Index," database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVK4-G1CT : 7 August 2020), Marion Foster Welch, ; Burial, Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States of America, Allegheny Cemetery; citing Find A Grave: Memorial #33321907, Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com.

- ↑ "State Song: 'Old Folks at Home'." Florida Department of State,.

- ↑ "Find A Grave Index," database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVV4-H6BK : 7 August 2020), Eliza Clayland Tomlinson Foster, ; Burial, Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States of America, Allegheny Cemetery; citing Find A Grave: Memorial #7910290, Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com.

- ↑ "Find A Grave Index," database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVV4-H6BL : 15 December 2020), William Barclay Foster, ; Burial, Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States of America, Allegheny Cemetery; citing Find A Grave: Memorial #7989577, Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com.

- ↑ "Find A Grave Index," database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVK4-L2DK : 7 August 2020), Dunning McNair Foster, ; Burial, Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States of America, Allegheny Cemetery; citing Find A Grave: Memorial #31933911, Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wikipedia contributors. "My Old Kentucky Home." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 Sep. 2022. Web. 20 Nov. 2022.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "Willie Has Gone to War." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 28 Mar. 2022. Web. 23 Nov. 2022.

- ↑ Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/360/stephen-foster: accessed 26 September 2022), memorial page for Stephen Foster (4 Jul 1826–13 Jan 1864), Find A Grave: Memorial #360, citing Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA; Maintained by Find a Grave .

- ↑ Burial: "Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, Allegheny Cemetery Records, 1845 - 1960"

citing Burial, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States, Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh.

FamilySearch Record: WC2M-74PZ (accessed 26 September 2022)

FamilySearch Image: 3Q9M-CS42-F3TP-G Image number 00253

Stephen C Foster burial (died on 13 Jan 1864 at age 36) on 21 Jan 1864 in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States. - ↑ Songwriters Hall of Fame

See Also:

- Stephen Foster's chronology, University of Pittsburgh

- Foster on The American Experience., PBS, Aired April 23, 2001.

Music

Oh! Susanna (1848) -- Performed by the 2nd South Carolina String Band

Old Folks At Home (1851) -- Sung by Tom Roush

My Old Kentucky Home (1853) -- Sung by John Prine

Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair (1854) -- Sung by Jan DeGaetani

Old Black Joe (1860) -- Sung by Paul Robeson

Beautiful Dreamer (1864) -- Sung by Bing Crosby

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Steven Marsden for starting this profile.

Click the Changes tab for the details of contributions by Steven and others.

No known carriers of Stephen's DNA have taken a DNA test. Have you taken a test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

- Anyone want to help with Stephen Foster profile? Feb 19, 2013.

Featured Asian and Pacific Islander connections: Stephen is 22 degrees from 今上 天皇, 17 degrees from Adrienne Clarkson, 20 degrees from Dwight Heine, 24 degrees from Dwayne Johnson, 21 degrees from Tupua Tamasese Lealofioaana, 19 degrees from Stacey Milbern, 21 degrees from Sono Osato, 30 degrees from 乾隆 愛新覺羅, 20 degrees from Ravi Shankar, 25 degrees from Taika Waititi, 24 degrees from Penny Wong and 16 degrees from Chang Bunker on our single family tree. Login to see how you relate to 33 million family members.

F > Foster > Stephen Collins Foster

Categories: American Musicians | Songwriters Hall of Fame | Songwriters | Composers | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | Persons Appearing on US Postage Stamps | Pennsylvania, Notables | Notables

I can remember as a child, about 9 years old, sitting in the library and reading books about him. (My mother was a classical pianist so I love music, although I do not play.)

In the 60's, when I was little, his songs were still very popular.

I think his profile should be protected in some way, an American Icon!!!