Contents |

Biography

Leo Buscaglia was an American author, motivational speaker, and a professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Southern California. He wrote more than a dozen books, primarily on the topic of love, selling more than 11 million copies in 20 languages.[1]

Felice Leonardo “Leo” Buscaglia was born on 31 Mar 1924 in Los Angeles, California. He died on 12 Jun 1998 in Glenbrook, Nevada.

Selected Works

- Love (1972)

- Because I am Human (1972)

- The Way of the Bull (1973)

- Disabled and Their Families: A Counseling Challenge (1975)

- Personhood: The Art of Becoming Fully Human (1978)

- Living Loving and Learning (1982)

- The Fall of Freddie the Leaf (1982)

- Loving Each Other (1984)

- Bus 9 to Paradise (1986)

- Seven Stories of Christmas Love (1987)

- A Memory for Tino (1988)

- Papa, My Father (1989)

- Born For Love (1992)

- Leo Buscaglia's Love Cookbook with Biba Caggiano (1994)

Research Notes

Biographical Sketch written by Leo's nephew, Albert Buscaglia:

Anyone who attempts to write a biography of my Uncle Leo will always have to face the difficult problem of dealing with the early years of his life (1924-1954.) I say this because, as everyone in the family knows, much of the “personal” information about Leo's early life that appears in his writings is not autobiographical information at all: it is a collective family history that has been restructured embellished and written to illustrate and support the “love” philosophy be began to develop in the early 1960s. Likewise, I also personally found out long ago that Leo was not really interested in accurately documenting his boyhood experiences in Boyle Heights or even be reminded about his experiences during World War II. For example I remember on one occasion when we were talking about my father, I asked him why he didn't write an autobiography and he answered, “I don't think it would be very interesting.” I disagreed with him, of course, but I did not press the issue because I knew that my father's view of family history was very different from Leo's view of family history. My father (the eldest child in the family) was brought to America from Italy in about 1910 and he did not learn to speak English until he started school in 1916. He did not become a citizen of the US until 1924. His childhood, I suppose, was like the childhood of most poor immigrant children at that time: the family moved from place to place; he was always the “new kid” on the block, other children made fun of him, he lived in crowded conditions, he literally had to fight to survive, his teachers found him unruly and disruptive, he was forced to, at an early age, to work at a variety of jobs and turned over his paycheck to his mother. He became an admirer of Bill Haywood and Upton Sinclair; and at the age of 20 he had to face the “Great Depression” of 1929. In contrast to this, Leo's life (as the youngest child) was much more stable and uneventful. By the early 1930s the Buscaglia family (Tulio, Rosa, Vinnie, Margie, Lena and Leo) had adapted to the American way of life. Things were still not easy for them, but they had established a permanent home on Fairmount Street and they were surrounded by good neighbors. It was here where they played and argued with their sisters. It was from here that they walked to the Wabash Theatre. It was at Fairmount St. that my father and Leo shared the same bedroom until 1935 and they ate with the family at the same long kitchen table. It was here that they finally established roots.

Everyone teased Leo by calling him “Felix the Cat.” On weekends, when the family could afford it, they took long streetcar rides to Ocean Park and Venice; and later, when the family acquired an old used car, my father would drive them to the beach in style with a trunk full of blankets, beach chairs and food. It is not surprising to me then that Leo would remember and make use of these and other pleasant family experiences in his writings. Likewise it is not surprising that Leo would also remember some of my father's childhood experiences and, in a sense, step into my father's shoes in order to relive and recreate in words the feeling of being an outsider. In a way, it was a special act of love. My father's view of family history of course could have been written by Theodore Dreiser and James T. Farrell. Uncle Leo's view of family history could have been written and directed by Frank Capra and Billy Wilder. I understand now that if they saw things differently it was because the formative years they experienced different aspects of American life. They were born 15 years apart. My father was a product of hard times, a product of the Great Depression. Having said all this, I am afraid that I cannot really shed much new light on Leo's early years.

Leo was never an important figure in his own house. In fact, even after his first book was published and he was acquiring a national reputation, his parents and some members of the extended family, Paul and Mario, were somewhat embarrassed by the things that he was saying. Paul and Mario in particular felt that old family friends (friends who knew Buscaglia family history) were laughing at them and asking if Leo was writing about some other people. As far as I know, however, no one in the family ever spoke with Leo about any of this.

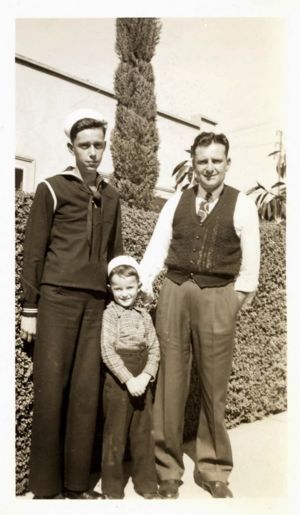

Whenever I think of my Uncle Leo, a number of old memories immediately flash across my mind. As a child, for example, I can still remember being taken to visit Leo while he was bagging groceries at Ralphs Market. I remember the last long hug that Leo gave me just before he left home to join the Navy. I remember those anxious years during World War II when we didn't know where he was or what he was doing. I remember hearing my father read Leo's letters. I remember seeing Leo in his uniform when he came home on leave. I remember the parties and picnics we had in the years after the war. I remember riding in his first car: a car he called “Aphrodite.” I remember being taken to see a one act play that he had written: a play that dealt with loneliness and the importance of love. I remember seeing Leo perform in Don Pasquale and some Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. And in particular, I remember the time that he took us for a ride to Laguna Beach in his “new car” and we got lost on the way home. In this instance, I can still see Uncle Leo telling us that he knew of a shortcut to the east that would get us back to Los Angeles thirty minutes sooner. I can still clearly see myself sitting in the front seat between Leo and my father as we started off. I can still see the greenish glow of the dashboard and I can still sense the presence of my mother and grandparents there in the dark behind us. It was only a little after 8 o'clock when we left Laguna, but by 9 o'clock it was already apparent that something was wrong. There were no freeways in the area at that time, and we drove on endlessly through the dark looking for a road sign or a gas station. We were all a bit tense, to say the least, but as we drove on and on without ever finding the shortcut, I remember hearing my mother and my grandfather joking about having to sleep in the car overnight. Their humorous remarks suddenly broke the tension and, though we still didn't know where we were going, we all began to enjoy what was happening. My father, Leo and my grandmother sang and old Piedmontese song that had something to do with traveling, my father told us about driving over the Torrey Pines Grade in the 1930s and even I was able to join in when my father and Leo began singing “Bye, Bye Blackbird.” Incredibly enough, we eventually ended up in Pomona and we didn't arrive home until 2 o'clock in the morning, but in typical Buscaglia fashion a misadventure had been turned into an enjoyable experience.

Most of my memories of Uncle Leo are tied to my childhood and I cannot really separate them from the memories of my father. I say this, of course, because it was my father who took me to the house in Boyle Heights where my grandparents and Uncle Leo lived; it was my father who did a great deal of the talking while we were there; and it was my father who usually planned family outings and other amusements. My father was very attached to his family and for as long as I can remember, we always visited the Buscaglias once a week. We did not have a telephone in those days and visiting was our only means of contact. Indeed for many years we spent one evening a week with my father's parents and one evening a week with my mother's parents. My father, however also set aside every Saturday for an extra special visit with his “brother Leo.” This special Saturday visit was apparently part of a Buscaglia family ritual. As a young man my father had always spent his Saturdays in downtown Los Angeles, and when Leo was old enough, he began taking him along as well.

These special visits with Uncle Leo always intrigued me as a child and after an endless amount of begging and years of waiting, my father finally allowed me to join him in 1949. Thus at the age of 11, I too was inducted into this Buscaglia family ritual: a ritual that (for me at least) was to last until about 1951.

Grand Central Market In describing this ritual I realize that it may seem like nothing more than just another Saturday shopping spree but in reality, for us, it was hardly a shopping spree at all because we had very little money to spend. Our purpose in going downtown (or at least I know wit was my father's purpose) was to rub shoulders with the “people.” My father always derived some kind of energy from just being in a crowd. He loved the contact, the noise, the smells, etc., the diversity and perversity that can only be found in the city. He enjoyed going fishing at the beach and he enjoyed going on a drive in the country, but he truly loved listening to rabble rousing in Pershing Square and riding on Angel's Flight. I can't say that I always shared my father's enthusiasm for the city, but I know that Uncle Leo did and the trips downtown were special because of what we saw and felt when we were together and not because of what we bought. I mention this because I know that my words are the bare outline of what we did and can never convey what we experienced on those special Saturday excursions.

The ritual would start at 8.30. We would usually pick Leo up at the Buscaglia's house on Fairmount St. and by 9.00 we would arrive at Hackett's garage and gas station. My father stopped at Hackett's because he had worked in the area in the early 1930s and knew many of the men who still worked nearby. At one time Hackett's had apparently been a gathering place for truck drivers and deliverymen, but business had fallen off in recent years and it was now just a rather rundown gas station. My father still went there however because an old friend of his worked there and we were allowed to park our car for free. One some occasions my father would meet other old friends at Hackett's and he would often spend a bit of time swapping stories while Leo and I looked on. Our stop at Hackett’s however was just a necessary preliminary to the real adventure, the walk “uptown.”

I can no longer remember exactly where Hackett's was located, but I do know it was a good distance from downtown Los Angeles and that we had to walk up “Skid Row” to get there. Uncle Leo sometimes referred to this aspect of the ritual as “running the gauntlet” because we had to make our way through what seemed like an endless line of pimps, prostitutes, panhandlers and drunks. I did not recognize the prostitutes for what they were, but I did know about panhandlers and drunks. No one really bothered us very much but there were times when we would have to walk around drunken men sleeping on the sidewalk.

Once again I can't remember how many blocks we walked, but eventually the squalor of Skid Row fell behind us and we found ourselves surrounded by department stores, jewelry stores, shoe stores, cafeterias and a very different class of people. It still amazes me when I think of all the places we visited and the miles that we must have walked. We stopped everywhere; we stopped at The Broadway, at the May Co., at the Eastern Columbia and even at Silverwoods where Leo and my father would check out the latest in men's clothing. They never bought anything there but the enjoyed looking at the merchandise. We also stopped at some Army surplus stores that were filled with pup tents and boots, bayonets, rifles and other leftovers from the war. The May Company however was perhaps our favorite place and after walking about upstairs for awhile we would enter the basement and look at he discounted books and articles of clothing. We always spent some time in the bargain basement. There were books down there and sometimes Leo or my father might buy one, or buy one for me.

By 11.45 or so when lunch time arrived, we usually ate at the Woolworth lunch counter or at “Wimpies” (my favorite) but there were occasions when we walked all the way over to Clifton's Cafeteria for a much better (and more expensive) meal. But this did not occupy a great deal of our time because we were always anxious to visit a number of other places: Pershing Square, the bookstore, the Grand Central Market, and most important for Uncle Leo, the record store. This began the best part of the ritual. I won't spend time talking about Pershing Square and the bookstores but I do want to mention the fact that Leo always bought a record or an album when we went to the city. Sometimes he would buy a classical work, sometimes he would buy a popular song and sometimes he would buy an Italian record that he knew his parents would enjoy. In this regard he was doing what my father had done for the family in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

It may seem hard to believe but I can still remember my grandmother's favorite songs. I can still remember that one record Leo bought for his parents was a popular Italian song by Carlo Butti called “La Piccinina.” I even knew some of the lyrics because I heard it played over and over again in the Buscaglia's living room. The Buscaglias enjoyed music of all types and Leo often played new records for us during our weekly evening visits.

There can be no doubt that by the time we left the record store we were all very tired (and I must admit that my first trip was a nightmare) but we still could not leave the city without shopping at the Grand Central Market. As a young man my father had always been expected to return from the city with fresh fruit and thus, even now, after he was married his mother still gave him a few dollars so that he could buy some specialty items for her. My father of course had worked in the wholesale grocery business for awhile and there were still a few vendors in the market who knew him and even added a few extra items or who gave him the “quality fruit” that only good customers received. Unfortunately it was not easy to get to the stalls where these vendors did business and we would have to follow my father and rub shoulders with the “people” in the most literal sense as we fought our way through the crowded aisles. There were thousands of unusual thing to see there – showcases full of all sorts of strange fish, sheep heads, pig heads, pig knuckles oxtails, etc. I was often tempted to break away and look more closely at these incredible things but my father told me, “Hold on tight to Uncle Leo's hand because you can get lost in here and we'll never find you again.” He was not lying! The market was an intricate maze filled with rivers of people.

The Grand Central Market was always the last stop on our visit to the city. When we left the market with our shopping bags full of fruit, we would once again make our way back across town and down through “the gauntlet” to Hackett's. We usually arrived at Fairmount Street at 3.30 and after bringing our shopping bags into the house, my father and I would return home.

In 1951 the Saturday ritual that I have just described was gradually supplanted by family trips to the beach. I am not sure why we stopped going to downtown Los Angeles, but the change at least made it possible for the whole family to be together for the whole day. We would leave at 9 o'clock in the morning and not get back until 10 o'clock at night. Long Beach was our favorite destination at this time, but we also went to Redondo Beach and even as far as Laguna on some occasions. Leo and my father enjoyed swimming and body surfing, and though I could not keep up with them in the water, I must say that it was always fun just being around them. We truly shared many wonderful moments in those days (swimming, eating the fresh fish and pasta that my mother and grandfather prepared, walking along the beach, etc.) but Leo's life was changing in the early 1950s, he had his own car, he was going to college, he was working at the library and was even writing plays and doing a bit of acting. We soon began to see him less often at home with his parents on our evenings with them. My grandfather said (speaking in Piedmontese) that Leo was “always running” and from our perspective he truly seemed to be running in many different directions at once. To be sure, he often came to our house for dinner; he also went with us occasionally to the opera; and he went with us to see certain important foreign films, (films like The Third Man and Miracle in Milan) but there was no longer any time left for lounging on the beach or wandering about in the Grand Central Market.

Contact with Leo grew even less frequent when he moved into his own home on Hayes Ave. We did occasionally visit him there; but more often than not, information about what Leo was doing came to us from my grandfather. By the early 1960s I moved to Texas and after that, I only managed to see Leo once or twice a year. Our meetings were still great fun and we talked for hours on end in order to make up for lost time. Leo, of course, had not yet published Love (1972) at this time, but he was already becoming something of a local celebrity by lecturing to various civic groups. Surprisingly enough, I did not learn about this aspect of Leo's life until my father sent me a newspaper article dealing with one of Leo's most recent lectures. The article, as I remember, directly quoted Leo on a number of occasions and it was apparent that the lecture revolved around Leo's view of Buscaglia family history. At the time, my father and I talked very briefly about the article over the telephone, but, a few months later when I returned to Los Angeles for the summer, he showed me another article (once again filled with quotations) and I suddenly realized that Leo's view of family history was very different from my father's view of family history. My father, for example, always talked about the “hard facts of life” when he mentioned his childhood, i.e. he talked about being hungry, he talked about living in a house crowded with relatives, he talked about never having a decent pair of shoes, and he talked about how his parents had to struggle to make ends meet. In effect, he always talked about the physical, social and emotional hardships that the Buscaglia family had been forced to endure. Uncle Leo, on the other hand, was talking about a different aspect of family life in his lectures, i.e., he was talking about the emotional strength, the humor, the ingenuity and the love that underpins human relationships. To be more specific, he was talking about the lessons he had learned from his family. I could see immediately from the quotations that some of his “personal experiences” he was talking about were not exactly autobiographical experiences; in other words I could see that they were part of a sort of collective or consolidated family history: a history where the experiences of many people merge into a unified first person narrative. But in any case, Uncle Leo's view of family history was dominated by a sense of charm and good will. To understand the difference on at least one level, I think, it is necessary to understand the environmental conditions that shaped them. My father died in 1975, and by that time Leo's life was becoming much more complicated and demanding: he was traveling, he was teaching, he was writing and he was lecturing every weekend in various parts of the country. Leo was not just “running” now, he was flying and no one in the family could keep up with him.

Sources

- ↑ Obituary: Leo Buscaglia dies at 74, Variety Magazine, 16 Jun 1998. Available online at Variety.com.

- Wikipedia. Leo Buscaglia <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Buscaglia> as viewed 19 June 2019.

- Wikidata. Leo Buscaglia <https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q2535504> as viewed 19 June 2019.

- Family Search. California Birth Index 1905-1995. Felice Buscaglis <https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:V25P-NZW> as viewed 19 June 2019.

- Family Search. United States Social Security Death Index. Leo F Buscaglia <https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:J5D5-5JX> as viewed 19 June 2019.

- Find A Grave, Felice Leonardo Buscaglia <https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14991304/felice-leonardo-buscaglia> as viewed 19 June 2019.

- Source: Geni World Family Tree Publication: MyHeritage The Geni World Family Tree is found on <A href="http://www.geni.com" target="_blank">www.Geni.com</A>. Geni is owned and operated by MyHeritage. Media: 40000 Collection <http://www.myheritage.com/research/collection-40000/geni-world-family-tree?s=216133531&itemId=34330314&action=showRecord&indId=individual-216133531-2000013>

- Source: Biographical Summaries of Notable People.Publication: MyHeritage The records in this collection vary in what data items are present and one will find information on various aspects of the subject persons including names, biographical descriptions, nationalities, birth dates, birth places, death dates, death places, relatives, spouses, children, professions, nationalities, and educational attainment. The information in this collection has been compiled from Freebase (under CC-BY) and Wikipedia (under the GNU Free Documentation License). Media: 10182 Collection <https://www.myheritage.com/research/collection-10182/biographical-summaries-of-notable-people?s=216133531&itemId=68456&action=showRecord&indId=individual-216133531-2000013>

It may be possible to confirm family relationships. Maternal line mitochondrial DNA test-takers:

- Gilbert Macagno

:

Family Tree DNA mtDNA Test HVR1 and HVR2, haplogroup HV, FTDNA kit #415839

:

Family Tree DNA mtDNA Test HVR1 and HVR2, haplogroup HV, FTDNA kit #415839

-

~25.00%

50.00%

Gilbert Macagno

50.00%

Gilbert Macagno  :

23andMe, GEDmatch T493038 [compare]

:

23andMe, GEDmatch T493038 [compare]

-

~3.12%

~6.25%

Michelle Mutschler

~6.25%

Michelle Mutschler  :

23andMe, GEDmatch XT9019738 [compare]

:

23andMe, GEDmatch XT9019738 [compare]

-

~3.12%

~12.50%

Peter McBride

~12.50%

Peter McBride  :

23andMe

:

23andMe

- Copied information on profile Oct 27, 2023.

Featured Eurovision connections: Leo is 32 degrees from Agnetha Fältskog, 30 degrees from Anni-Frid Synni Reuß, 28 degrees from Corry Brokken, 19 degrees from Céline Dion, 29 degrees from Françoise Dorin, 31 degrees from France Gall, 32 degrees from Lulu Kennedy-Cairns, 28 degrees from Lill-Babs Svensson, 25 degrees from Olivia Newton-John, 36 degrees from Henriette Nanette Paërl, 36 degrees from Annie Schmidt and 22 degrees from Moira Kennedy on our single family tree. Login to see how you relate to 33 million family members.

B > Buscaglia > Felice Leonardo Buscaglia

Categories: Glenbrook, Nevada | University of Southern California, Professors | Lake Los Angeles, California | United States Navy, World War II | California, Notables | Notables | Italian Roots